Text Compression with Neural Networks

Can we use AI to make compression better? Yes we can! In this post I outline a compression algorithm for English text built on top of GPT-2 that achieves an order of magnitude better compression ratio than gzip (and is several orders of magnitude slower to run 😉)

Introduction: Compression and Language Models

At a very high level, compression works by identifying and exploiting patterns and redundancies in the source message. A common approach in compression is to use more compact codes for more common inputs - for example, you might compress English text by using fewer bits for common letters (like ‘e’), and more bits for rare letters (like ‘q’). Similarly, some character sequences are more common than others: for example ‘th’ is very common in English, while no words contain ‘tq’. Most lossless compression algorithms like gzip work by exploiting these kinds of byte-level patterns[1].

In addition to patterns at the character level, English has a lot of higher-order structure, at the word and sentence level. For example, at the word level, vowels in English carry little information. Therefore: mst ppl hv n trbl rdng ths sntnc. At the sentence level, consider the phrase: “I was born in France, then moved to Germany when I was 15. I still speak fluent _____.” As humans, we can confidently guess the last word is most likely “French”.

Generally speaking, a language model is a probability distribution over a sequence of words. That is, given some previous words in a text, a language model tells us what is the probability the next word is w? A straightforward usecase for this is autocomplete on your smartphone keyboard and (more recently) when composing emails in Gmail. It is possible to build a simple language model using n-grams, but recently neural networks have become very good at generating convincing text. A famous, recent, successful example of this is GPT-2 from OpenAI (take a look at some of the samples in that post to see how convincing this model is)

Using a language model for text compression

The fact that language models work means they can capture some of the structure in language. So, how can we exploit this structure for compression? A simple scheme might be the following: type out the input text on your smartphone keyboard, and every time the keyboard’s next-word prediction is correct, replace that word with a special character (let’s use underscores for now):

Input: It's a nice place to work with friends.

Compressed: It's a nice _ _ work with friends. On my phone, after typing “It’s a nice “, SwiftKey suggests “place” as the main (middle) suggestion, so we can replace “place” with an underscore. Since the underscore is shorter than any word it might replace, the compressed message is shorter than the original. As long as I have access to the same keyboard (language model), and if it is deterministic, I can reconstruct the original text by replacing underscores with whatever the main suggestion is from the language model.

But we can do even better: the phone keyboard actually has 3 suggestions, not just one. Therefore, we might be able to compress even better by encoding runner-ups as well:

Input: It's a nice place to work with friends.

Compressed: It's a nice _0 _0 work _1 friends. In this case, “with” was the second suggestion, so we can compress it as _1 (we’ll keep things zero-indexed). If the on-screen keyboard offered even more autocomplete suggestions (say, the top 10 runner-ups), we would have even more opportunities for compression.

Trying this out with a language model

Instead of a phone keyboard, I’ll use GPT-2, because (1) it’s a much more powerful model, (2) it’s easier to work with, and (3) it’s open source.

Broadly, this is what I did:

- Start with some English text (I used the full text of Alice in Wonderland)

- Split the text into words, and assign each word a number. GPT-2 has a dictionary of 50,000 words, so we’ll end up with a sequence of numbers between 0 and 50,000. [2]

- For each word in the text:

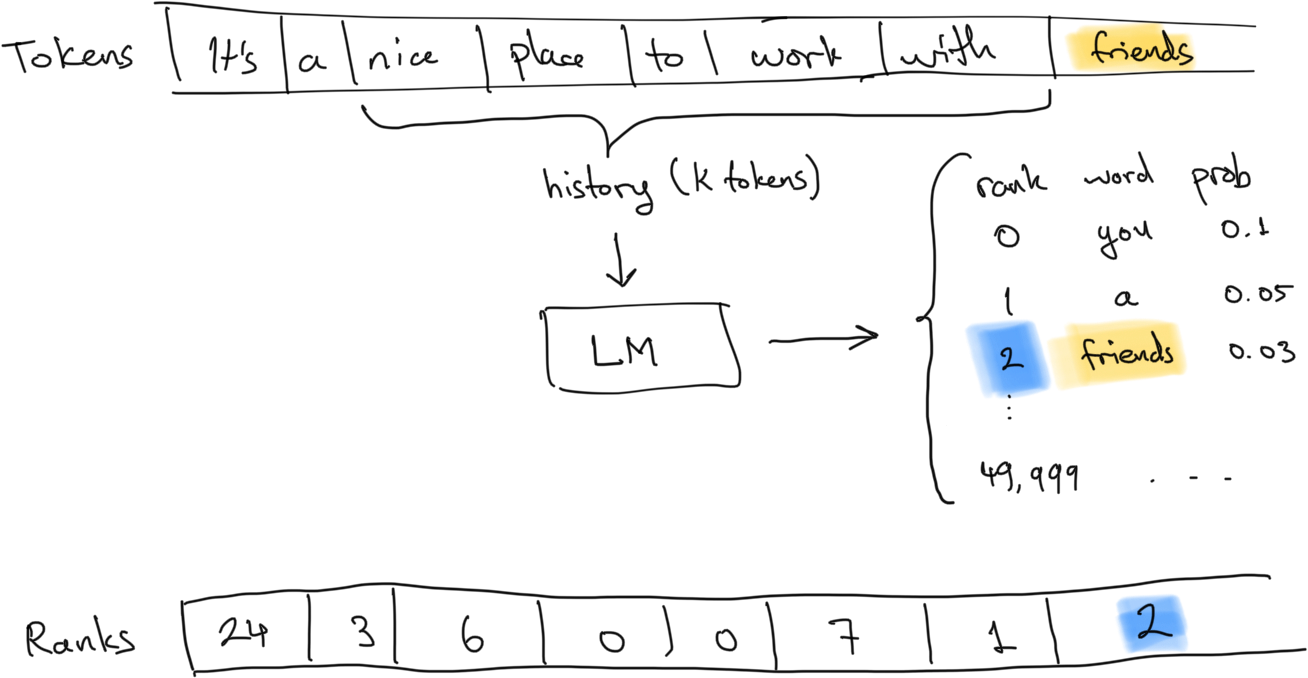

- Show the language model the last k words, and ask it to predict the next word. It will output a probability for each of the 50,000 possible words in our dictionary.

- Sort the output by probability, and figure out the rank of our word. In our previous example, “place” would have rank 0 because it was the top prediction, and “with” would have rank 1 because it was the runner-up.

- Instead of compressing the IDs of each word, compress the IDs of each word’s rank.

By doing steps 1 and 2, we converted our original n-word text into a sequence of n integers. Step 3 still gives us n integers, so on the surface it’s not very helpful. However, the hope is that the latter sequence is more compressible.

The intuition for this is, a repeating sequence (like “aaaaaa”) contains less information and is therefore more compressible than a completely random sequence (like “auxhkwp”). If our language model were perfect, the rank for all the words in the document would be zero, and the resulting sequence ([0, 0, 0, ...]) would be highly compressible.

Let’s visualize the token and rank distributions to check if our intuition holds.

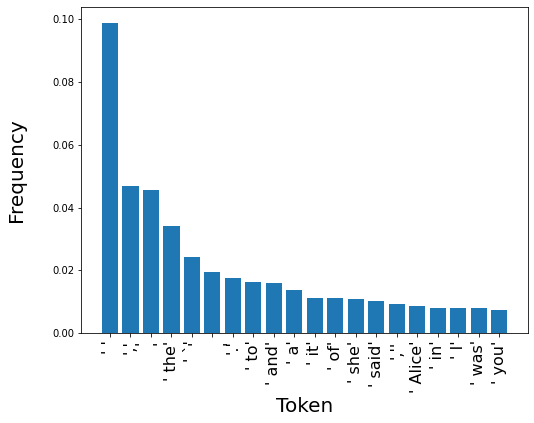

Token Frequency

Let’s take a look at the distribution of the 20 most common words (more precisely, tokens). As expected, a lot of it is punctuation and stopwords. In total, the top-20 most frequent tokens account for 42.6% of all the tokens in the text.

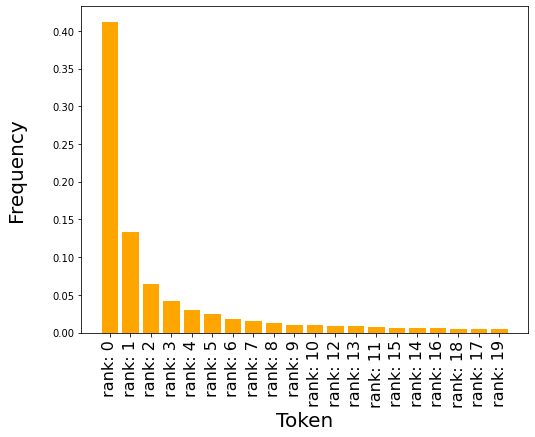

Rank frequency

As we hoped, the distribution of the word ranks drops off much more quickly, and the top-20 ranks account for 82.8% of all the tokens.

As an aside, note that a good langauge model, we expect lower-ranks (i.e. higher-probability tokens) to occur more frequently. This is mostly true here, though there are some exceptions - for example, the actual next token is the 12th likeliest slightly more often than the 11th likeliest.

Comparing entropy

This intuition is formalized in information theory, as entropy. Broadly speaking, a distribution has more entropy if sampling from it is more informative. For example, tossing a fair coin ({H: 0.5, T: 0.5}) gives us 1 bit of information, whereas tossing a completely biased coin ({H: 1.0, T: 0.0}) gives us 0 bits – it tells us absolutely nothing new. Another interpretation is that we need 1 bit to store the result of one fair coin toss.

Using scipy.stats.entropy: the distribution of tokens has 8.44 bits of entropy, and the distribution of ranks has only 4.37 bits. In other words, because the distribution of ranks is less informative, it should take fewer bits (that is, less space) to encode each token.

Compressing ranks from the language model

Information theory tells us that the ranks should theoretically compress better than the token IDs. In particular, it tells us that each token should take up 8.44 bits compressed, and each rank should take up about 4.37 bits. (As a comparison, uncompressed, each token takes up log_2(50_000) = 15.61 bits, or just under two bytes).

How can we achieve this compression in practice? In Python, we could try using the builtin zlib function:

import zlib

import struct

def compress_short_ints(shorts):

byte_parts = [struct.pack('>H', short) for short in shorts]

bytearr = b''.join(byte_parts)

return zlib.compress(bytearr)This reduces the tokens sequence to 48,138 bytes, and the ranks sequence to 33,377 bytes. There are 42,579 tokens in the sequence, so this implies ~9 bits per token, and ~6.3 bits per rank. This is a nice result, as it confirms that the ranks sequence is more compressible than the tokens sequence. However, the performance still seems suboptimal: theoretically, we expect every rank to compress down to ~4.37 bits, not 6.3.

One source of inefficiency is that zlib does bit reduction at the byte level, but we work with tokens of two bytes. Just to check if this is right, let’s build our own compressor. I used Huffman coding because the dahuffman library is available on pip and easy to use, but it should be possible to get even better results with arithmetic coding. In Python:

from dahuffman import HuffmanCodec

from collections import Counter

def huffman_compress_short_ints(shorts):

freqs = Counter(shorts)

codec = HuffmanCodec.from_frequencies(freqs)

return codec.encode(shorts)The tokens sequence now compresses to 45,143 bytes (8.47 bits per token), and the ranks sequence to 23,487 (4.41 bits per rank). Much better!

What about the frequency table?

Note that we’re cheating a little bit above, because we also need access to the frequency table to decompress the message. In general, there are two ways to tackle this: (1) use the same frequency table for all messages, or (2) prepend a unique frequency table to each compressed message. The first approach makes a lot more sense here, because we expect the frequency table to be very similar between messages.

Conclusions

Using the tricks described in this article, we managed to compress Alice in Wonderland from 148,481 to 25,600 bytes. This is 2x better than gzip (53,654 bytes) and xz (47,876 bytes).

That compression and building ML models are related is not a new idea. In fact, the website for the Hutter Prize, an ongoing competition for effective compression of text data, recognizes as much: they are motivated by the observation that “being able to compress well is closely related to acting intelligently.” This specific approach wouldn’t qualify for the Hutter Prize, because the GPT-2 model is too big. There is some academic work on using language models to compress text, as well as a very easy-to-use implementation (which unfortunately isn’t open-sourced).

Appendix: How do I actually run GPT-2?

For this project, I used Huggingface Transformers because it lets me easily swap out different trained language models.

Even though the purpose of a language model is to output the next token (singular; only one token), a lot of documentation out there is about language generation (i.e. generate many tokens). Maybe this makes sense considering GPT-2’s claim to fame is generating realistic-sounding text given only a short prompt. I found Huggingface’s blog article on generating text to be an extremely good introduction to this topic. For our purposes, a good summary is that, if our goal is to generate realistic text, continuously outputting the most-probable next token is just about the worst thing you can do.

Transformers provides a seemingly very straightforward way to generate text:

from transformers import AutoModelWithLMHead, AutoTokenizer

tokenizer = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained("gpt2")

model = AutoModelWithLMHead.from_pretrained("gpt2", return_dict=True)

input = "It's a nice place to work with"

input_ids = tokenizer.encode(ss)

generated = model.generate(input_ids, max_length=len(input_ids[0])+1)

last_token = generated[0][-1]

generated_word = tokenizer.decode(last_token)However, this only gives us the most likely last word, and there’s no easy way to get generate to return multiple samples (though the above article on generating text is great for explaining what the myriad different arguments do).

Digging through the docs, it turns out we can get the model’s next token probabilities:

next_token_logits = model.forward(input_ids).logits[:, -1, :]

last_token = torch.argmax(next_token_logits[0])

generated_word = tokenizer.decode([last_token])However, this is still inefficient because it causes us to rerun the model inference for overlapping sequences. For example, if we use a history of 20 tokens (i.e. len(input_ids) == 20), we would have to call model(input_ids[0:20]) for the first prediction, model(input_ids[1:21]) for the second prediction, and so on. To get around this, I had to modify the source code of the forward function to iterate through the actual tokens (not generated ones) and return the probability distribution on each pass.

Another practical consideration is batching: the model runs much faster with batches of tokens, rather than taking a single vector of tokens at a time. This is straightforward for compression, as we can split the input linearly into any number of consecutive batches. However batching is not possible for decompression, because we can’t decompress later batches without first knowing the preceding text. This means we can either make decompression unbatched (and therefore slower), or have multiple starting points (one starting point for each batch), requiring the model to warm up more times (and therefore achieve a slightly lower compression ratio).

Footnotes:

-

The DEFLATE algorithm used in gzip has two parts: first it looks for and eliminates repetitions using LZ77, and then it does bit reduction using Huffman coding. ↩

-

GPT-2 actually uses Byte Pair Encoding with a vocabulary size of 50,000 words, so the tokens are not necessarily complete words. In practice, though, most tokens are complete words. ↩