Networking and simple HTTP servers

Most of us come across computer networking concepts all the time, whether setting up websites, setting up docker containers to talk to each other, or debugging distributed systems. I realized my networking fundamentals are a bit lacking, so I spent a few hours reading and building.

Motivation: understanding networking

I came across a post on Hacker News about how routers work. This reminded me that I don’t actually know how computer networking works at all. I went on a short reading spree and here are a few interesting things I learned:

- How the OSI model differs from common TCP/IP stacks.

- How the

pingutility operates on the network layer (OSI level 3, over ICMP) and that’s why it doens’t have a port allocated. - How DHCP works (it relies on broadcasting because there are no IPs assigned yet).

- The IP header has a protocol field, which specifies whether the packet is TCP or UDP (or something else). This means I can have two different services use the same port number, one over TCP and one over UDP. (And this is why firewalls need me to specify both the port and the protocol.)

- Wireshark is a thing, and it’s actually really useful to visualize and debug these things.

- Building an application server is actually not that hard, and quite educational.

For this post I want to focus on the last bullet point. I spent a couple hours and built a super simple HTTP server [1] in python, that just serves some static content. This was a great way to learn about sockets and what it means to persist connections. I also now understand exactly what HTTP headers are, and I even got to review some multithreading!

Let’s build an HTTP server!

For me, the purpose of this exercise was to understand the networking parts a bit better, so I built everything on top of TCP sockets.

In Python, listening to a socket is actually pretty simple:

import socket

sock = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM) # AF_INET for IPv4, SOCK_STREAM for TCP

sock.bind(("127.0.0.1", 12345))

sock.listen()

connection, client_address = sock.accept() # blocks until a client connects

data = connection.recv(16) # blocks until 1 or more bytes are received; reads up to 16 bytes

connection.sendall("send some bytes".encode("utf-8"))

connection.close()Side note: you can test this with telnet, e.g. telnet localhost 12345

So how many bytes should I expect to read?

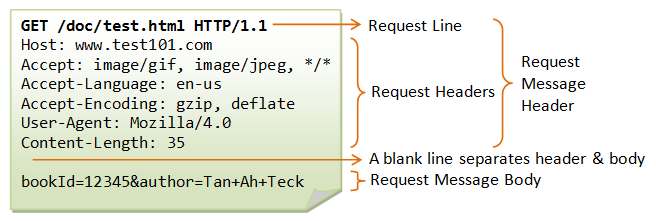

In the snippet above, we don’t actually know how much data to expect when we call connection.recv(). The HTTP protocol solves this by basically saying (1) expect more headers until you see an empty line, (2) if there is a body following the headers, its length will be specified by the Content-Length header.

Similarly when we send responses, we have to make sure we also send the length as a header.

What about text encoding?

In HTTP, headers are encoded in ascii, and the content / encoding of the body is specified in headers.

What about concurrent requests?

In the snippet above, sock.accept() opens a TCP connection with a client. We can listen for new connections in a loop, and once a connection is established, we can spin up a new thread to handle it:

while True:

connection, client_address = sock.accept()

worker = threading.Thread(None, target=handle_connection_fn, args=(connection, client_address))

worker.start()

def handle_connection_fn(connection, client_address):

# TODO handle requests from this connection

connection.close()It was satisfying to see this work by making handle_connection_fn deliberately slow (e.g. time.sleep(5)) and watching multiple requests get handled in parallel.

What is session persistence?

Opening a TCP connection is relatively slow because we need to perform a TCP handshake. So, if the client and server agree, they don’t have to close the TCP session (connection.close()) after each request, but instead can keep it open. Let’s fire up wireshark to see what this looks like in practice:

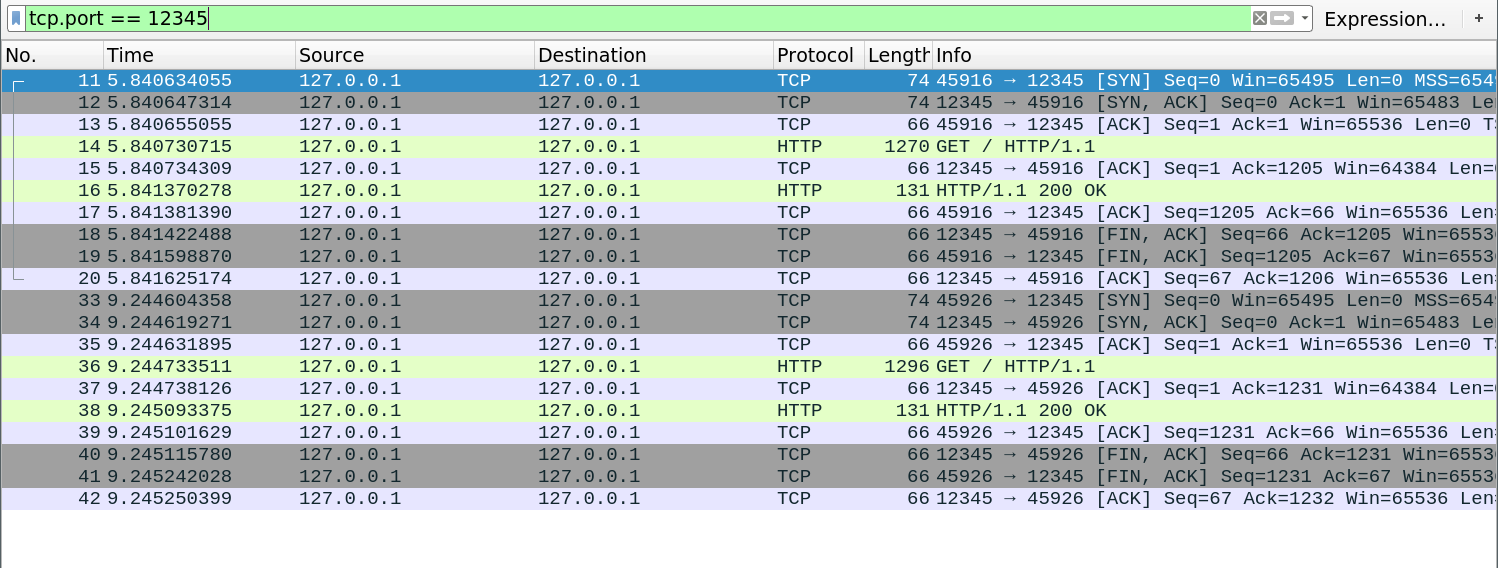

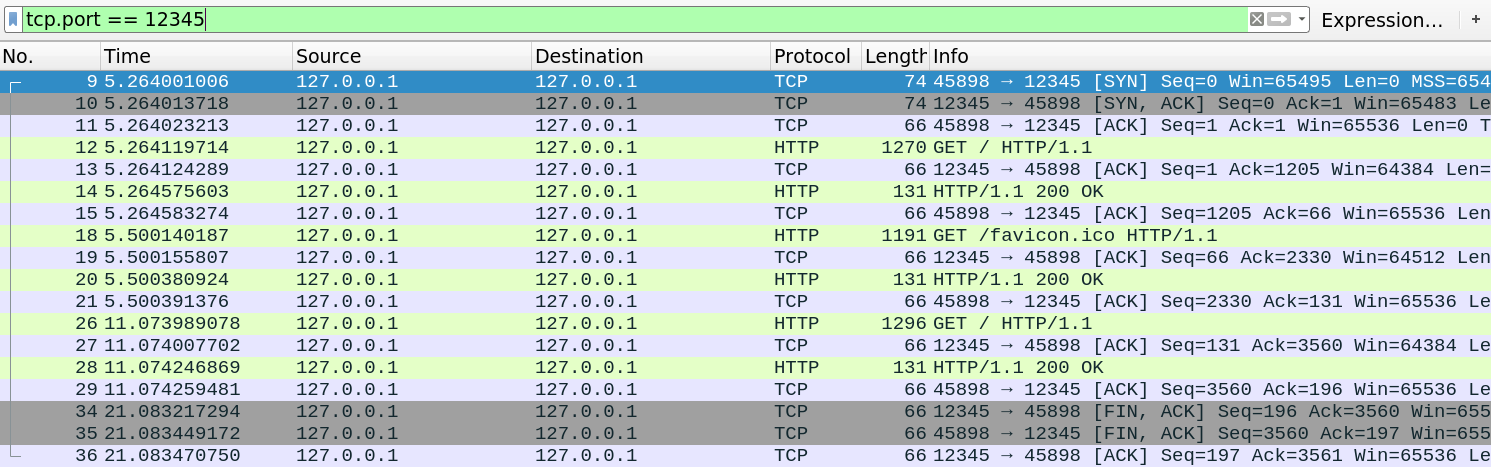

The first screenshot is with the server closing the connection immediately after handling it (no keepalive), and the second is with keep-alive.

This is what two requests look like with keepalive disabled. Notice the TCP handshake and disconnect packets (gray) surrounding the HTTP requests and responses (green):

However, after enabling keepalive, we see that subsequent requests (generated by refreshing the browser) happen inside the same session and there is no TCP handshake overhead:

The keepalive behavior was made standard in HTTP/1.1, while in HTTP/1.0 servers were expected to close the connection unless the client set the Connection: keep-alive header.

How fast is it?

So far I tested my server in a web browser, but I can also use a utility like curl. To estimate performance, I could write a small script to send a bunch of requests via curl, but it turns out there are already good server benchmarking tools. I used ApacheBench: ab -n 5000 -c 5 -s 1 http://localhost:12345/ showed me my server implementation can serve ~2k requests per second. If I turned off threading, this jumped to about ~4k. This implies the overhead to start/stop a new thread is around 0.5ms, which feels a bit high to me but isn’t completely unreasonable. Overall the performance isn’t amazing considering nginx can handle over 10k req/s on the same machine and also implements many more features, but performance wasn’t a design goal here.

Setting a high concurrency to ApacheBench (e.g. -c 500), I saw that some requests failed and ApacheBench spit out some errors like apr_pollset_poll: The timeout specified has expired (70007). Using Wireshark to track this down, I realized this happens for requests where the server doesn’t acknowledge the connection quickly enough and so there are long pauses between TCP retries. ApacheBench seems to forget about and ignore these connections, leading to hangs or very long timeouts. At first I thought this exposed a bug with my server, but I managed to get the same behavior with nginx.

I also played with loadtest.js, which seems to do a better job on reporting bad connections. However, it runs in Javascript and uses 100% of one CPU core so I don’t entirely trust its performance metric.

Conclusion

I built a very simple HTTP server and learned a bunch of random things about networking and the HTTP protocol. It turned out to be a great way to spend 3 hours. The code I wrote is available as a gist but it’s extremely hacky so I don’t recommend reading it.